When we’ve been a part of a church for any length of time we can get used to hearing and using some phrases which we would never use in any other context. There are good reasons for this; often they are found in the bible, or in the songs we sing (which often take phases from the bible anyway!). This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. We are often trying to express complex or abstract ideas and sometimes simple, functional words just won’t do.

Whereas it is up to us to try to make ourselves understood when talking to others, and we should use normal, modern language if trying to talk to non-believers about God, there is actually a vast store of treasure to be discovered in the passages we read and the words we sing – if only we can crack the code!

…there is actually a vast store of treasure to be discovered in the passages we read and the words we sing – if only we can crack the code!

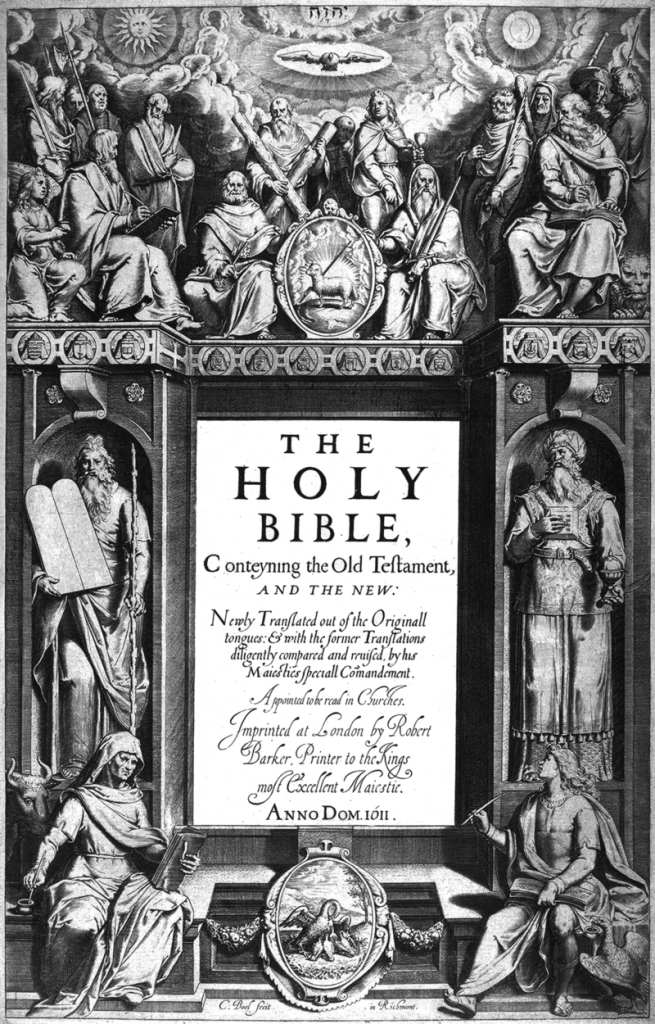

The version of the bible many Christians grew up with (I would say older Christians, but I count myself in their number) is the Authorized Version (AV), sometimes called the King James Version (KJV). It is called the Authorized version because it was, upon its completion in 1611, authorized by James I to be read in the Church of England. It has remained in popular use until recent times, and many people still prefer certain passages from it to those in newer translations. Some of the phrasing is poetic and beautiful, but the language is now 400 years old. Just like reading the works of Shakespeare, it can be difficult to understand, but there is much to be gained if you can speak the language.

Frontispiece to the King James’ Bible, 1611, shows the Twelve Apostles at the top. Moses and Aaron flank the central text. In the four corners sit Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, authors of the four gospels, with their symbolic animals. At the top, over the Holy Spirit in a form of a dove, is the Tetragrammaton “יהוה” (“YHWH”). The title page text reads: THE HOLY BIBLE, Conteyning the Old Teſtament, AND THE NEW: Newly Tranſlated out of the Originall tongues: & with the former Tranſlations diligently compared and reuiſed, by his Maiesties speciall Comandement. Appointed to be read in Churches. Imprinted at London by Robert Barker, Printer to the Kings moſt Excellent Maiestie. ANNO DOM. 1611 . At bottom is “C. Boel ſecit in Richmont.“

Here’s an example of what I’m talking about. We often say the ‘Lord’s Prayer’ together. Many of us have recited this from our school days, and we still do so in church today. It is sometimes referred to as the pattern prayer, as it reminds us of the type of things we should be praying; acknowledging God’s authority, praise, for God’s will to be done, petition, strength to do what is right, confession, forgiveness and more praise. There is so much more to be said about this, but that will have to wait for another time. What we are looking at now is the language. This is how it appears in the AV:

After this manner therefore pray ye: Our Father which art in heaven, Hallowed be thy name. 10 Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven. 11 Give us this day our daily bread. 12 And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors. 13 And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil: For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, for ever. Amen.

And this is as it appears in The Message:

Our Father in heaven,

Reveal who you are.

Set the world right;

Do what’s best—

as above, so below.

Keep us alive with three square meals.

Keep us forgiven with you and forgiving others.

Keep us safe from ourselves and the Devil.

You’re in charge!

You can do anything you want!

You’re ablaze in beauty!

Yes. Yes. Yes.

As a little aside, notice that the AV doesn’t say ‘forgive us our trespasses’ as we usually do when we recite it, but debts. This is worth taking a look at another time, but trespasses was the preferred word of William Tyndale in his translation in the time of Henry VIII.

Anyway – back to the words which are used:

which art = who is – nothing too difficult so far

hallowed = greatly revered and honoured. For me, this one word is full of intensity: special, beyond a simple word for word translation.

I don’t think there are any other words in this which would cause a problem in themselves, but it is still worth appreciating the imagery in the language which goes above literal translation. We ask for our daily bread, but in fact if we found ourselves in financial trouble, unable to pay for our rent/mortgage, amenities or car but with some bread, we may not feel that we asked for enough! To me, our daily bread means the necessities of life. In this country I’d argue that includes a roof over our heads and electricity. God knows this. He isn’t petty, and a prayer isn’t a magic spell that must be pronounced precisely in order to work. If we ask for our basic needs to be met by using the words ‘daily bread’, God will understand.

I’ll leave things here for now. I hope that this has provoked a little thought about the meaning of the words we say and sing. We’ll look in a little more depth at some songs in the future and see what treasure we can find as we pull them apart!